The below is a review of select data presented at the recent

5th Joint Triennial Congress of the European and Americas Committees for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis... also known as ECTRIMS.

And so I wanted to share it with you because I thought it had some fantastic nuggets of good information for my patients with MS.

As you look this over, be patient with me. No one likes unwieldy graphs, but these are pretty straight forward and they are summarized as well. But I think that if you or your loved one have MS, I believe it's reasonable for me to expect you to gather the patience to wade through some graphs created for you.

ECTRIMS this year had a number of presentations looking at how to optimize our currently existing disease-modifying therapies, treatments for acute relapses, and symptom management. Although a lot of attention is paid towards the future therapies, I think maximizing what we have available to us today is crucial.

The main purpose of this is really to establish the efficacy in clinically isolated syndrome (to see if works at helping prevent a one-time event from actually turning into MS).

A secondary purpose of this trial is to demonstrate the efficacy of

The outcomes of this looked at the development of MS by the McDonald criteria, which has become the standard way of looking at diagnostic certainty for multiple sclerosis (especially for all research studies to make the diagnosis is uniform across the planet). I should add that they used the McDonald 2005 criteria, as opposed to the more recently developed 2010 criteria; this trial was run well before that most recent criteria was produced (although the new criteria isn't too significantly different).

The primary outcome data showed that with NO TREATMENT (placebo medication) the median time to convert to McDonald MS was 97 days (about 3 months).

On interferon 44 μg given once a week, it was 182 days (half a year).

And, on interferon β[-1a] 44 μg given three times a week, it was 310 days (2 months shy of a year).

This shows a reduction in the risk of conversion to MS of 31% in the weekly interferon dose (a third less likely) and 51% in the three-times-a-week interferon dose (half as likely).

This outcome is important for a couple of reasons. One, it further provides confirmatory evidence that interferon β-1a is a viable treatment strategy after a first attack, or the CIS, versus placebo. I think it also provides support for the three-times-a-week dosing schedule versus weekly interferon [β]-1a.

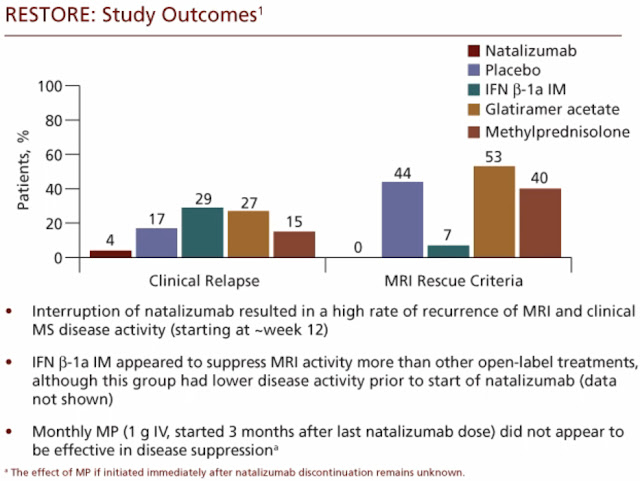

The RESTORE trial was seeking to evaluate the effect of natalizumab (Tysabri) treatment interruption on the clinical course of patients with MS (In other words, what happens if we stop Tysabri due to health concerns?)

In short, there has been a lot of consternation in our field in the past couple of years about how long to keep patients on natalizumab, what with the recognition of the increasing risk of the awful PML with increasing duration of exposure to the drug (The longer you're on the medication, the more likely you are to get PML). This trial was done specifically to look at what are the risks of discontinuation of natalizumab to sort of counterbalance the concerns about the risks inherent in continuing a patient on natalizumab (getting PML as a risk of continuing versus return of MS by stopping).

So this trial looked at patients who'd been on natalizumab and have it discontinued, followed by placebo infusions (fake medication), and then a series of open-label rescue therapies (any interferon or other real medication used to treat MS) to see if disease activity recurred. Disease activity here was described as both clinical activity—changes in EDSS [EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale] scores—or MRI disease activity, consisting of new gadolinium (contrast)-enhancing lesions.

In brief, what this study ultimately showed is that stopping natalizumab confers an increased risk of the return of disease activity in multiple sclerosis. There were a substantial number of relapses and an even more substantial number of MRIs showing the resurgence of disease activity in the weeks and months that followed natalizumab cessation. In particular, the highest rate of recurrence of disease activity seemed to appear at around week 12, after natalizumab was discontinued.

This provides some supportive data to the notion that stopping natalizumab therapy brings about a somewhat riskier period of time for MS patients when disease activity may return.

It does not answer the question as to how to treat these patients after natalizumab is stopped, nor does it provide specific guidance in regards to which patients should be maintained on natalizumab for a longer period of time. But I do think it provides some supportive evidence to know that patients in whom natalizumab has been stopped, for whatever reason, need to be observed closely and likely treated promptly with other

The vitamin D story in multiple sclerosis has evolved rapidly over the last several years. It has long been recognized that there is a latitudinal gradient to the incidence of MS with higher incidence seen further from the equator.

The role of direct sunlight and, therefore, natural generation of vitamin D being more prevalent near the equator has been one hypothesis for this difference in the incidence of MS.

Subsequently, epidemiologic studies of patients have shown that there may be a correlation between chronically low vitamin D states and the development of multiple sclerosis in otherwise more homogenous populations. Due to this, a lot of attention has been turned to vitamin D to see whether it, in fact, correlates with the development of MS and the severity of MS, and whether, perhaps, treating with supplements of vitamin D can be disease modifying.

Studies presented at ECTRIMS looked at the effects of endogenous and supplemental vitamin D in patients with MS. And they found that, for every

Supplemental vitamin D3 decreased

Turning to symptom management in multiple sclerosis, pain is a very commonly reported symptom of MS, and many studies have shown that it has significant impacts on quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis.

This study looked at the use of duloxetine (Cymbalta) in the treatment of central neuropathic pain in MS patients. And the study was positive and showed a greater improvement in the pain index scores for duloxetine versus placebo-assigned patients, although there was a significant placebo effect on pain. But duloxetine did have better outcomes in a statistically significant way than placebo at controlling central neuropathic pain in the patients studied here.

This trial provides information that duloxetine and this class of medicines may very well have a role for pain management in multiple sclerosis. As we have seen, other comorbidities and related symptoms in MS that are very common include depression and anxiety. And, although these things weren't studied as outcomes in this trial, the utilization of a medicine that may also help to treat depression and anxiety, as well as pain symptoms, may be a very useful strategy in a number of MS patients with several

Before we fully turn our attention to the emerging therapies on the horizon, it's important to think about maximizing the efficacy and outcomes of our currently existing therapies across the needs of MS patients.

We also have to carefully balance the benefit-to-risk ratio of our medicines in the long-term for MS patients. A lot of attention has been turned to the risks of our medicines, such as the risk of PML with natalizumab. The trial we discussed talks a bit about the other side of that risk equation: What are the risks inherent in MS when a treatment like natalizumab (Tysabri) is discontinued? Showing there that stopping natalizumab therapy does seem to result in a high rate of recurrence within the first 12 weeks after the treatment is stopped.

And the vitamin D story continues to evolve with data now suggesting that not only are lower levels of vitamin D related to higher levels of MS disease activity, as shown on MRI, but, in fact, treating with supplementary vitamin D may exert a significant protective effect in this regard.

Finally, looking at symptom management, duloxetine (Cymbalta) appears to be a viable management option to treat central pain syndromes that are so often seen in multiple sclerosis.